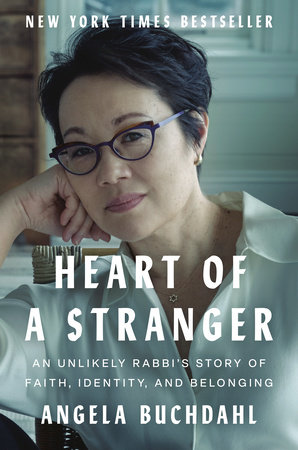

I read about the first Asian American Rabbi, Angela Buchdahl, in an article talking about her visit to San Francisco synagogue. She was promoting her recently published book, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging. I haven’t yet read her book, and to learn more about her, I listened to the interview embedded above. Buchdahl tells a fascinating story about her journey from as a biracial child in Seoul to becoming a highly influential and followed rabbi. She is the senior rabbi of a Central Synagogue, major synagogue in Manhattan. The Central Synagogue’s YouTube channel has over 70,000 subscribers.

I read about the first Asian American Rabbi, Angela Buchdahl, in an article talking about her visit to San Francisco synagogue. She was promoting her recently published book, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging. I haven’t yet read her book, and to learn more about her, I listened to the interview embedded above. Buchdahl tells a fascinating story about her journey from as a biracial child in Seoul to becoming a highly influential and followed rabbi. She is the senior rabbi of a Central Synagogue, major synagogue in Manhattan. The Central Synagogue’s YouTube channel has over 70,000 subscribers.

The notion of being a “stranger” resonates with me as an Asian American. The title made me think of another book, Strangers from a Different Shore by Ronald Takaki. It also reminded me of the feeling of many Asian Americans that they feel that they don’t fit in in either Asia or in the United States. In the interview, Buchdahl tells the story of playing with Korean children when she was a child. They asked her where she was from, and she said to them in Korean that she was from Korea. The other children told her that she was not.

There are a lot of interesting subjects discussed in this interview, including her views on the new New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani and on the relationship between disagreements, debate, and democracy in US society. It’s an hour long, but well worth the listen.

I first heard of the film

I first heard of the film

The

The

Many news outlets across the country have reported how burglars target Asian Americans for robbery.

Many news outlets across the country have reported how burglars target Asian Americans for robbery.

When going through the list of films I might possibly see during

When going through the list of films I might possibly see during