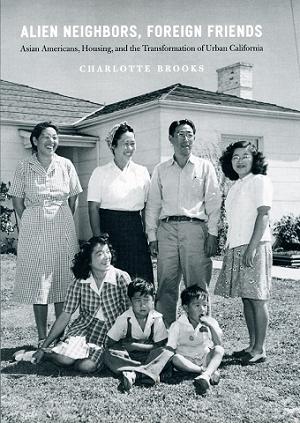

The progression of rights for Asian Americans in California has had more change in the last 100 years than most people realize. Charlotte Brooks has a new book out, Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California (University of Chicago Press, 2009) on evolution of attitudes towards Asian Americans in California.

The progression of rights for Asian Americans in California has had more change in the last 100 years than most people realize. Charlotte Brooks has a new book out, Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California (University of Chicago Press, 2009) on evolution of attitudes towards Asian Americans in California.

Here’s the book description:

Between the early 1900s and the late 1950s, the attitudes of white Californians toward their Asian American neighbors evolved from outright hostility to relative acceptance. Charlotte Brooks examines this transformation through the lens of California’s urban housing markets, arguing that the perceived foreignness of Asian Americans, which initially stranded them in segregated areas, eventually facilitated their integration into neighborhoods that rejected other minorities.

Against the backdrop of cold war efforts to win Asian hearts and minds, whites who saw little difference between Asians and Asian Americans increasingly advocated the latter group’s access to middle-class life and the residential areas that went with it. But as they transformed Asian Americans into a “model minority,” whites purposefully ignored the long backstory of Chinese and Japanese Americans’ early and largely failed attempts to participate in public and private housing programs. As Brooks tells this multifaceted story, she draws on a broad range of sources in multiple languages, giving voice to an array of community leaders, journalists, activists, and homeowners—and insightfully conveying the complexity of racialized housing in a multiracial society.

This book is a good reminder about our not too distant past, and how Asians couldn’t own property in much of California as late as 1968 when the Fair Housing Act was passed. I’ve written in another blog article about the surprise I had when purchasing my first home in San Jose (which was built in 1963), and the CC&R’s I had to sign that indicated I could not own, nor live in my own home as an Asian American, unless I was a servant to the “white” owner of the house. Those CC&R’s are of course not enforceable under today’s laws, but the documents remain tied to the history and records of the home.

After I wrote that blog article I was told about a Japanese American original owner of an Eichler home in Cupertino, also built in the early 1960s. He relayed a story about how Eichler was the only builder in the San Francisco Bay Area that did not write CC&R’s that prevented Asians and other minorities from purchasing homes. I researched Joseph Eichler some more after that discussion and found out from Wikipedia:

Unlike many developers of the day, Joseph Eichler was a social visionary and commissioned designs primarily for middle-class Americans. One of his stated aims was to construct inclusive and diverse planned communities, ideally featuring integrated parks and community centers. Eichler, unlike most builders at the time, established a non-discrimination policy and offered homes for sale to anyone of any religion or race. In 1958, he resigned from the National Association of Home Builders when they refused to support a non-discrimination policy.

Eichler homes are often criticized for their design, but finding out about Joseph Eichler’s commitment to equality has given me a new found respect for these modern-design homes. Housing discrimination is part of our past and one that’s not well known, so I was glad to see a new book published that covers this topic.

Charlotte Brooks’ new book has received many positive reviews and it’s worth a look if you’re interested in the history of Asian Americans in California from the 1900s onwards.