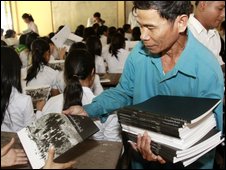

Tuesday, 11 November, students at Sisowath High School received the first copies of a textbook detailing the autogenocide led by the Khmer Rouge regime in the years 1975 – 1978. Published by the Documentation Center of Cambodia, this textbook replaces five lines written on the Pol Pot era in current history books. Due to the changing political climate of the country, teaching about the events during Democratic Kampuchea has been anything but straightforward. With the Khmer Rouge retaining political influence well into the mid-1990s and former cadres occupying government roles, an honest portrayal of this period has been scant and gradually minimized from public education. This textbook comes also with the documentation of testimonies from the on-going Khmer Rouge tribunals conducted some 45 minutes outside of Phnom Penh.

Tuesday, 11 November, students at Sisowath High School received the first copies of a textbook detailing the autogenocide led by the Khmer Rouge regime in the years 1975 – 1978. Published by the Documentation Center of Cambodia, this textbook replaces five lines written on the Pol Pot era in current history books. Due to the changing political climate of the country, teaching about the events during Democratic Kampuchea has been anything but straightforward. With the Khmer Rouge retaining political influence well into the mid-1990s and former cadres occupying government roles, an honest portrayal of this period has been scant and gradually minimized from public education. This textbook comes also with the documentation of testimonies from the on-going Khmer Rouge tribunals conducted some 45 minutes outside of Phnom Penh.

Considering that I had the benefit to take an Asian American Studies course and learn about the genocide, I find it to be an odd privilege to possess this knowledge in light of the release of this textbook. In the United States, many Khmer Americans either seek to hear the stories of their parents, sometimes successful and other times not; or maybe never think to ask because their parents fall silent on why they ever came to the US. Public k-12 education also has not been a reliable institution to learn about a genocide that occurred partly in reaction to a US-supported ruler.

I find it shocking that many young people in Cambodia today do not believe the stories of their elders surrounding the genocide. It only makes more salient the notion of what is the “official record” that is accepted history. Who writes the textbooks, who is left out, who is valorized — such factors have significant impacts on how a generation is raised. Hopefully this textbook will correct a dangerous historical amnesia in Cambodia’s up and coming new leaders. With almost half the population under the age of 20, I believe the imperative of knowing one’s history is even more marked in Cambodia. The author of the textbook expressed, “The young generation has the responsibility to repair this broken glass. They need to understand what happened in their country before they can move forward to build up democracy, peace and reconciliation.”