After my grandparents answered “No No” to questions 27 and 28, the whole family was sent to Tule Lake, Northern California. A camp that was designated for “bad” Japanese Americans – in other words those who had answered the loyalty questionnaire negatively or had caused “trouble.”

After my grandparents answered “No No” to questions 27 and 28, the whole family was sent to Tule Lake, Northern California. A camp that was designated for “bad” Japanese Americans – in other words those who had answered the loyalty questionnaire negatively or had caused “trouble.”

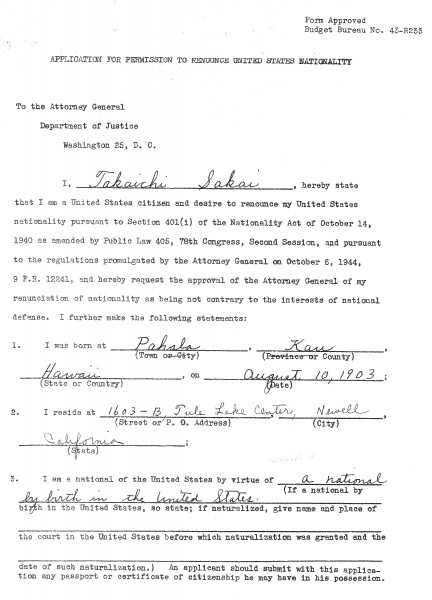

It was in Tule Lake that my grandparents, and thousands of Japanese Americans like them, willingly gave up their American citizenship and asked to be sent to Japan. His decision would forever brand him a traitor – within the Japanese American community and the nation at large.

Here is a copy of his application to renounce his citizenship:

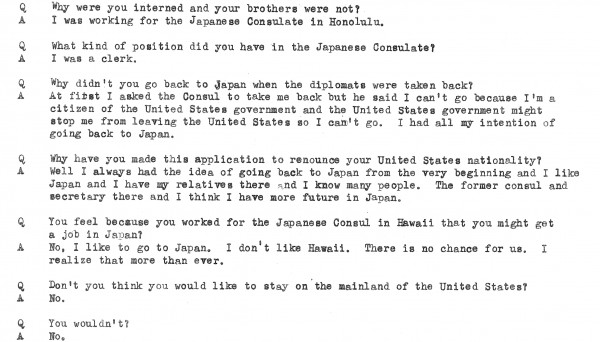

And while he was trying to renounce his citizenship, he said anything that would ensure that he got his wish. In this transcript of the renunciation of citizenship hearing, he said the following:

I never knew whether he gave up his citizenship willingly or because of outside pressure. Without being able to ask him, I could only assume he was so upset and bitter about the events after Pearl Harbor, he preferred to be in war-torn Japan than his native country.

And the thing is, I would have been bitter too. All my life I’ve been taught about equal rights, the Constitution/Bill of Rights, and how America is the home of the free and the land of the brave… only to find out that it’s not for everyone and can change depending on whom we are currently at war with. In that light, if I were my grandfather and everything that happened to him had also happened to me, I may have made the same decision.

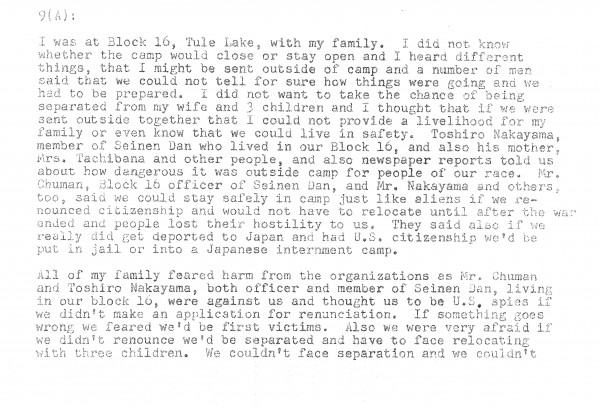

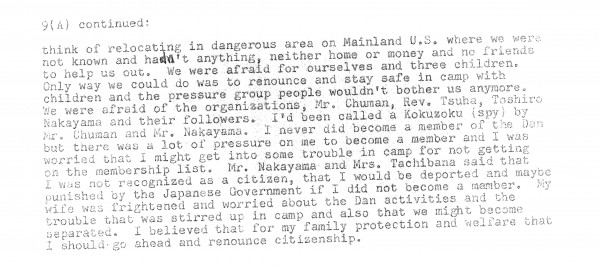

But in the FBI file that I found, he explained (in his own words) why he renounced his citizenship.

(That might be difficult to read, so let me transcribe it for you below)

9(A):

I was at Block 16, Tule Lake, with my family. I did not know whether the camp would close or stay open and I heard different things, that I might be sent outside of camp and a number of men said that we could not tell for sure how things were going and we had to be prepared. I did not want to take the chance of being separated from my wife and 3 children and I thought that if we were sent outside together that I could not provide a livelihood for my family or even know that we could live in safety. Toshiro Nakayama member of the Seinen Dan who lived in our Block 16, and also his mother Mrs. Tachibana and other people, and also newspaper reports told us about how dangerous it was outside of camp for people of our race. Mr. Chuman, Block 16 officer of Seinen Dan, and Mr. Nakayama and others too, said we could stay safely in camp just like aliens if we renounced citizenship and would not have to relocate until after the war ended and people lost their hostility to us. They said also if we really did get deported to Japan and had U.S. citizenship we’d be put in jail or into a Japanese internment camp.All of my family feared harm from the organization of Mr. Chuman and Toshiro Nakayama, both officer and member of Seinen Dan, living in our block 16, were against us and thought us to be U.S. spies if we didn’t make an application for renunciation. If something goes wrong we feared we’d be first victims. Also we were very afraid if we didn’t renounce we’d be separated and have to face relocating with three children. We couldn’t face separation and we couldn’t think of relocating in dangerous area on Mainland U.S. where we were not known and hadn’t anything, neither home or money and no friends to help us out. We were afraid for ourselves and three children. Only way we could do was to renounce and stay safe in camp with children and the pressure group people wouldn’t bother us anymore. We were afraid of the organizations, Mr. Chuman, Rev. Tsuha, Toshiro Nakayama and their followers. I’d been called Kokuzoku (spy) by Mr. Chuman and Mr. Nakayama. I never become a member of the Dan but there was a lot of pressure on me to become a member and I was worried that I might get into some trouble in camp for not getting on the membership list. Mr. Nakayama and Mrs. Tachibana said that I was not recognized as a citizen, that I would be deported and maybe punished by the Japanese Government if I did not become a member. My wife was frightened and worried about the Dan activities and the trouble that was stirred up in camp and also that we might become separated. I believed that for my family protection and welfare that I should go ahead and renounce citizenship.

Similar to the “No No answer” (see part 3), his reason for giving up his citizenship was more nuanced than I had assumed. The most striking thing to me about his explanation was that it was NEVER about disloyalty or hatred of America. His decision was based on bad information, fear of separation of his family, fear of the Japanese Government, and fear of other Japanese Americans in Tule Lake.

Maybe because I’m looking at all this 70 years later, but renouncing his citizenship seems like it was a terrible mistake. He thought it would make it easier on him in the long run, when it fact, it made it much much much more difficult for him and the entire family later. One of the worst things a citizen can do is give up their citizenship willingly and my grandfather did it. No matter what his reasons, once done, it is very difficult to undo.

Maybe because I’m looking at all this 70 years later, but renouncing his citizenship seems like it was a terrible mistake. He thought it would make it easier on him in the long run, when it fact, it made it much much much more difficult for him and the entire family later. One of the worst things a citizen can do is give up their citizenship willingly and my grandfather did it. No matter what his reasons, once done, it is very difficult to undo.

Civil Rights attorney (and personal hero), Wayne Collins, fought for renunciants like my grandfather. According to Japanese American History: an A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present , Collins argued that the nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) were “coerced into renouncing their citizenship for several reasons:

- a small clique of Japanese nationalists were terrorizing those who did not renounce their citizenship;

- the government knew of these terrorists and not only did nothing about it, but actually aided them;

- the government, through its “inhuman” treatment of the internees, brought about extreme duress which was responsible for such behavior.”

Points 1 and 2 are very much in line with what my grandfather wrote: “We were afraid for ourselves and three children. Only way we could do was to renounce and stay safe in camp with children and the pressure group people wouldn’t bother us anymore.” And when you add the fact that he had lost all of his civil rights and (as far as he knew) was going to be incarcerated indefinitely, it is not difficult to see why he made the decision that he did.

- Part 1: The United States vs. Takaichi Sakai: Crimes

- Part 2: The United States vs. Takaichi Sakai: No No

- Coming up next week: The United States vs. Takaichi Sakai: The Decision, Part 4 of 5