The generally accepted Japanese American narrative goes something like this: We came to this country. There was discrimination. Then Pearl Harbor happened. We went peacefully to the concentration camps and then while there we remained docile and peaceful. Some fought bravely in Europe and helped win the respect of the country which 50 years later resulted in an reparations and an official apology.

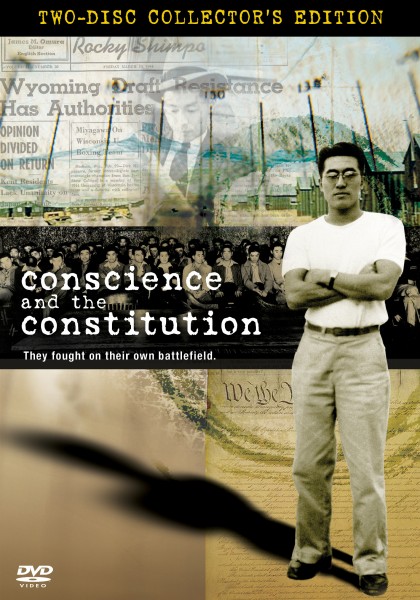

While a lot of that is true, there was also a group of people in the 1940s that decided to fight for not only their rights but for all Americans. They questioned the constitutionality of what was going on and by doing so many of them were jailed and ostracized, especially within the Japanese American community. Unfortunately, their story remains relatively unknown. That’s why Frank Abe’s documentary, Conscience and Constitution, about the brave people who were willing to stand up for their rights, is so important.

Conscience and Constitution is an award-winning film for PBS reveals the untold story of the largest organized resistance to the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, and the suppression of that resistance by Japanese American leaders.

I had a chance to sit down with Frank and ask him about his documentary.

For those who didn’t see Conscience and the Constitution when it originally aired in 2000, what is it about?

It’s about young men, boys really, who were called upon to take a stand as men. It’s about following your gut and taking an unpopular stand even when your family and community tell you to lay low and don’t make trouble. It’s about making a choice when confronted with a government order you know is not right – do you comply, or do you resist? And it’s about crossing the line, from protest to resistance.

Who were the resisters? And why should people know about them? What relevance do the resisters have today?

When I first met them, they struck me as ordinary guys who could have been an uncle or family friend. In fact, I later discovered that Mits Koshiyama and Kozie Sakai were in the same minyo Japanese folk-singing circle as my mother.

But go back to 1944, and they were one of 85 young men who refused to be drafted from the American concentration camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. They were ready to fight the Nazi’s in Europe – Mits would have joined his brother overseas – but not before the government restored their rights as citizens, freed their families from camp, and let everyone go home to LA, Fresno, Seattle.

In storytelling terms, they were the classic ordinary people thrust into extraordinary circumstances. But not only did they each search their souls and decide to risk five years in prison and disgrace to their families in order to stand on their principles – at Heart Mountain they organized. And Heart Mountain was the only one of the ten camps where that happened.

At other camps – and here I get myself in hot water with friends with fathers at those other camps – the protest of the draft resisters was less focused and their message could be mistaken for something easier to demonize. At Heart Mountain they organized as the Fair Play Committee and quoted Abraham Lincoln and the Bill of Rights in articulating a clear case based on the Constitution.

And they went to court as a group of 63 not because they were crazy about bucking the draft, as they put it, but because they were using the recently-enacted Selective Service Act of 1940 to force a test case on the underlying question of mass exclusion based solely on race. This was in 1944, after spending two years in camp, and as Yosh Kuromiya said, if they didn’t take a stand at that point, it would mean accepting their forced incarceration as legal. As one of the new outtakes says, it was “The Largest Mass Trial in Wyoming History.”

I finally saw Captain America this weekend. Never having read Marvel Comics or Nick Fury (I was more of a DC Comics kid), I never knew of the Jim Morita character, the Nisei soldier (“Hey, I’m from Fresno”) freed from the Nazi’s prison who joins the Captain’s howling commandos. And a lot of young viewers will think that’s cool, that the movies fleetingly acknowledge the Nisei as an archetype, along with the Brit and the African American soldier. But Jim Morita volunteered from a camp, or from Hawaii where they had one small camp. As we say in the film, the Nisei soldiers were brave, but their valor did not address the constitutional questions raised by the camps. The resisters took on that question head on, and they paid a price: two years in camp, two years in prison, and a lifetime of social ostracism within the Japanese American community. And that’s what I hope that young audiences can also get to know.

It’s relevant because mass exclusion is going to happen again. Not necessarily to us, maybe not in our lifetimes, but to some other readily identifiable group that can be isolated and demonized at a time of crisis and fear. And when that happens, you’re going to find leadership that emerges that says it’s better to accommodate the mob in order to get better treatment, and, one hopes, others who reject accommodation and collaboration.

Tell us a little bit about how you got interested in the subject matter

In high school and college, once I finally read more about the camps and Heart Mountain to fill out what little my father would say about it, I searched for signs of resistance. It only made sense to me. It was the 60s of course, and I think any baby-boomer Sansei’s reaction was like, uh, why didn’t you guys resist going to camp? But there was nothing like that in any of the published accounts of the time, and there were no oral histories. And when kids like me asked about that, the Nisei would kind of pat us collectively on the head and say you weren’t born then, you don’t know how it was, you can’t judge us with your Berkeley-civil rights-activism of the 60s.

Then Frank Chin – who was then my mentor in all things Asian American, from theater to John Okada to redress – flew up Frank Emi and James Omura to Seattle at his own expense in the early 1980’s to meet with a few of us here, to introduce them and get us interested in their story. And finally I could see they were the missing link But it wasn’t until a decade later that we got serious about telling their story as a documentary.

For those who have already seen the documentary, what’s new about this two-disc DVD set?

I’m glad you asked, because that’s what I’m most excited about – two hours of bonus material that we just couldn’t shoehorn into the 56-minute running time of the film that aired on PBS. I’ve spent the last three years nights and weekends building great stories from a treasure trove of material – our raw interviews and sequences we didn’t use from early rough cuts.

When you play through the bonus features it’s like watching a second movie that runs in parallel with the original. The new features give viewers a chance to hear more about the trial of the resisters; hear James Omura’s amused observation of a frightened Mike Masaoka urging cooperation; hear Mako sing the Song of Cheyenne composed by the resisters in a county jail; and see Yosh and Irene Kuromiya return to the spot where he sketched Heart Mountain as a kid, which was also the moment that inspired an off-camera Lawson Inada to compose the title poem in his collection, Drawing the Line. These features also allowed us to get in a lot of the stills, documents and paraphernalia we gathered for the film but never used.

New for the DVD are the actual prison mug shots of the seven Fair Play Committee leaders who were imprisoned at Leavenworth federal penitentiary in Kansas. That was a huge find we made after the film aired, thanks to a relative of Kiyoshi Okamoto. We also solved the mystery of the mystery woman who acted as a go-between between the Fair Play Committee leaders in camp and newsman Jimmie Omura in Denver.

One new feature of special interest to scholars is the release of highlights from a radio interview I did with wartime JACL leader Mike Masaoka in 1988, when he came through Seattle for a JACL convention and to promote publication of his autobiography. All I want to say about that is, you have to hear it for yourself.

We shot one bit of new material with the help of videographer Curtis Choy as a sequel or post-script to the story: the ceremony in San Francisco where the JACL publicly apologized to the resisters for demonizing them and trying to crush their movement during the war. Frank, Yosh and Mits took the whole apology movement with a grain of salt – in fact you can see how Frank Emi used his platform at the event to press his case for JACL to apologize to the entire Japanese American community – but there’s no denying that the event brought more media attention to the story and brought out from seclusion a number of the Nisei resisters in the Bay Area who had been avoiding interviews and public recognition. And for these less-visible resisters, the JACL apology was a meaningful public acknowledgement of their courage for themselves and especially for their grown children.

How can people watch the film? And what can people do to help you spread the word?

For at least the first year of release we’re going to self-distribute the DVD set through our website, www.resisters.com, and in particular for the college and library market through Transit Media in New York at (800) 343-5540.

Where we need help the most is in getting colleges and universities to acquire the DVD for institutional use – for American history, law, and Asian American Studies departments. Getting the DVD into libraries and classrooms puts the story in front of students at the time they’re learning about World War II or constitutional law. The resisters were a classic example of civil disobedience in the American 20th century. All the bonus features are primary materials from which students can draw for their research. It’s a resource that wasn’t available when my generation was growing up.

To watch it now, we have video clips up for viewing at YouTube/ConscienceDVD. You can follow us on Twitter at Twitter.com/ConscienceDVD. And we’d appreciate readers sharing this 8Asians post through Facebook and other social networks, and by Liking our page at Facebook.com/ConscienceDVD.

Frank Abe is a former senior reporter for KIRO Newsradio and KIRO-TV, the CBS affiliates in Seattle. In his 14-year career he wrote and produced numerous reports, broadcast live from Japan, Korea and Thailand, and produced a weekly series featuring writers of color, “Other Voices.” He won numerous awards from the Asian American Journalists Association, the Washington State Bar Association, the Society of Professional Journalists, the Academy of Religious Broadcasting, and others.

Abe helped produce the first-ever “Day of Remembrance” in 1978 with Frank Chin and Lawson Inada, and together they invented a new Japanese American tradition by producing car caravans and media events in Seattle and Portland that publicly dramatized the campaign for redress. “Days of Remembrance” are now observed as an annual event wherever Japanese Americans live. Abe was project director in 1980 for a series of successful public symposiums, “Japanese America: Contemporary Perspectives on the Internment,” funded by the Washington Commission for the Humanities. Abe supervised the editing and publication of the proceedings of those events, and produced a radio documentary drawn from the testimony.

Abe is a former National Vice-President of the Asian American Journalists Association, and taught broadcast writing at Seattle University. He was a founding member of the Asian American Theater Workshop in San Francisco, studied at the American Conservatory Theater, and was featured as an internment camp leader in John Korty’s 1976 NBC-TV movie, Farewell to Manzanar.

“My own father was interned at Heart Mountain. Only recently did I learn that he donated $2 to the Fair Play Committee and subscribed to the Rocky Shimpo to read James Omura’s editorials.”

More recently Abe has served as communications director for former King County Executive Gary Locke, the Metropolitcan King County Council, and the current County Executive, Dow Constantine.