The first national organization to speak out against the illegal incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II was the Quakers. The Quakers have a long standing commitment to progressive causes. Many don’t know this but they were one of the first groups to fight to abolish slavery and have advocated for women’s rights and later civil rights as well. (To see some of the causes they are currently fighting for, click here.)

The Quakers have a long standing commitment to progressive causes. Many don’t know this but they were one of the first groups to fight to abolish slavery and have advocated for women’s rights and later civil rights as well. (To see some of the causes they are currently fighting for, click here.)

Although the Quakers were the only national group to come out against the Japanese American concentration camps, that’s not to say that all the people were for it. There were some brave (non-Japanese/Japanese American) people who were willing to put themselves (and their reputations) on the line for the rights of Japanese Americans.

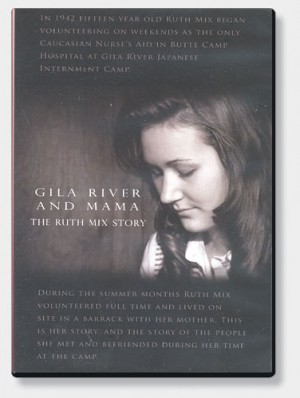

Two such persons were Frieda and Ruth Mix. I recently saw Gila River and Mama: The Ruth Mix Story, a wonderful documentary about these two extraordinary women. I had a chance to sit down with the director (and the granddaughter/daughter of these two women) and ask her 8Questions:

Tell us about your grandmother, mother, and of course yourself.

My grandmother Frida was a progressive thinker and often went against the grain of society. She was a suffragist, and

marched for the woman’s right to vote. She was arrested two times for marching. The second time she was arrested she was nine months pregnant with her eldest son. I say this with a smile, because I am so proud of my grandmother. I mean when you think about it, how many people do you know can say that their grandmother marched in the suffrage movement? Grandmother was always fighting against bigotry, and when I say fight, I don’t mean with her fists. She was a pacifist, a small woman with a very gentle voice and demeanor, she used her voice to bring about reason, and forward thinking, and she reached many people. She worked as a school teacher in a one room school house in Wenatchee Washington. There, she taught her girl students how to live more independently, and think independently – including her own daughter, my mother, Ruth Mix.

My mother carried the same philosophies that my grandmother, and the same strength of will. But where my grandmother used her words to educate bigoted people, my mother would use her fist. When mom was in her teens and younger, and she met someone who said some off-color remark about a particular race, or poor people, or someth

ing sexist, mom would flat out punch them in the face. She was always getting in trouble for fighting. She learned to use “words” when she entered college. And where my grandmother would use gentle words and intellectualism to better enlightened a person, my mother used her words as if she was throwing a punch. For example… I remember attending a social gathering with my mom back in 1970s, I think I was about 14. Somebody at the party, amidst all the chitchat going on, remarked that they thought it was a good idea that Pres. Roosevelt interned all the Japanese Americans. My mother looked at this person and said, “Have you always been a jackass or did you have to work at it?”

As for me, I am a mixture of both my mother and grandmother. I was a lot like my mother when I was young, always getting into fights. I never got in trouble for fighting because it was always in defense of somebody who was being teased or bullied. There was a chubby girl in grammar school, a girl that I still know to this day and who is my friend, who was constantly bullied for being chubby. One day I walked right up to the main bully, a boy two years older than me, and kicked him so hard between the legs that my toes hurt for a week, (but I’m sure he hurt for much longer). After that he never bothered her again. It wasn’t until I entered college that I learned to use my “words” and I did not use my words to throw a punch, that’s where I was more like grandmother; I was calm and tried to use more intellectualism. I’m a teacher, like grandmother, as well.

How did your grandmother/mother feel about the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II? What did they decide to do about it?

My grandmother was outraged, completely incensed. My mother didn’t quite understand the whole story about what was happening at first, she was more confused. But the more she learned, she shared my grandmother’s feelings, naturally. My mother told me that grandmother said, “We must right this terrible wrong, and help them.”

My grandmother joined a group of teachers, that happened to be Quaker, and with my mother in tow, she resigned from her teaching position in Wenatchee to volunteer as a teacher in Gila River internment camp. My mother volunteered as a nurse’s aide at the camp hospital, which was called Butte camp hospital. And she was the only Caucasian nurse’s aide there.

How long did your grandmother/mother end up staying in the camps? And why so long?

My grandmother stayed at the camp until the camp finally closed, which was a few months after the war ended I believe. My mother was there almost all four years of the war, she had to leave about six months earlier because of a life threatening lung infection she got because of all the dust. Many, many people died because of lung infections because of the dust at Gila River, including children.

What was the reaction of the rest of your family and people outside of the camp to your grandmother’s decision?

My mother said they were looked at by society “as though they were martians.” When they would step off the bus to go shopping in town of Mesa, people would shout to them, “Jap lover or Jap sympathizer,” and whole host of other terrible names. They were refused service at a few shops, too.

My grandmother’s older sister was outraged and embarrassed that she would go and take her daughter with her to the desert of Arizona. My aunt and did not have the compassion of my grandmother, nor the intellect.

My mother had three older brothers, who all went off to war to fight. My mother’s brother Merrill actually volunteered at Gila River as grandmother’s teacher assistant for about a month until he was shipped out.

My mother and grandmother were social outcasts during the war, simply due to the fact that they disagreed with the internment and volunteered at a camp to help these American citizens of Japanese ancestry.

Tell us about your documentary. What is about? How did you get off the ground?

My documentary primarily focuses on my mother’s memories about working in Butte camp hospital, and about camp life, and her friends. I interviewed her in 2007. After years of asking for her to talk about her experience, she finally agreed due to the fact that she had been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, and she knew her time would be short. She died six months after the interview.

The documentary was funded by a generous grant from the California State Library through the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program.. They realized this story was a unique internment story, because it was coming from a perspective of a Caucasian, teenage volunteer – my mother was only 15 years old when she started working at the hospital.

Ben Tonooka and Hy Shishino and the Gila River Reunion Committee were instrumental with fund raising, as well as the dozens of people who donated independently. Ben and Hy were executive producers; they believed it was an important story.

Charles Class, a friend of my mom for 50 years, also executive produced, and keeps the ship sailing right. Without his knowledge, I’d be lost.

How has the Japanese American community responded to it?

I have received bundles of letters from Japanese Americans who remember my mother and grandmother, and they say the loveliest things. I received e-mail after e-mail from people who were interned, who simply poured their heart out in these letters about how this documentary touched their lives. I received a letter from one woman who was interned at Gila, who stated that while she was there and even to this day, she felt everyone hated her because she was of Japanese ancestry. After watching my documentary she said a great weight had been lifted from her heart, because she didn’t know that there were many, many Caucasian people who cared, and did not think that she was the enemy, nor did they hate her. I have since spoken to this woman on the telephone, and now we communicate on a regular basis – sometimes with tears of sorrow and sometimes with tears of joy.

As more people see the documentary, the more letters pour in; all very positive and emotional.

The response from the non-Japanese American community, has widely been “Wow! I didn’t even know about the Japanese American internment,” which doesn’t surprise me, it is not talked about in history classes as it should be.

What advice do you have for young activists fighting for the rights of others?

Do what my grandmother did, and right whatever terrible wrong is being done to people. Fight the peaceful fight, but never stop fighting. See it to its end, until there is change. It takes a lot of guts to go against the grain. It takes strength to speak up when nobody else will. My mother was 15 years old when she spoke up. She gave up her teenage years, all through high school, she gave up dances, her prom, parties, and any kind of social life that one has in their high school years, all to defend American citizens of Japanese ancestry who were so unjustly incarcerated during World War II. Until the day mom died, she didn’t regret a moment of it, and wished she could have done more.

What are you working on next?

I have recently completed the young adult novelization of my mother and grandmother’s experience at Gila River. It’s entitled The Girl with Hair Like the Sun. It includes a great many details that were not covered in the documentary. I’m hoping it will be available to the public, and placed in public school libraries by 2012.

I am also co-writing the screenplay version with an extraordinarily talented writer in Los Angeles. We feel it is an important story to tell and that there is much to be learned by their experience.

To find out more about the documentary, please visit their official website or Facebook pages.