This post was originally published on ThoughtCatalog and has been republished here with permission.

By Ruth

I suck at games. I don’t have the attention span to memorize the rules of poker. I don’t have the agility to compete in any kind of physical sport without irony. And I sure as hell can’t get into any kind of video game that requires me to inhabit the body of an ax-wielding elf. In fact, the only games I have mastered are Uno, Pictionary, and Foosball: activities that require nothing but a steady hand and zippy flick of the wrist. People usually don’t engage me in competition.

It used to come as a surprise to me, then, when complete strangers would recruit me in a game I like to call “Guess Her Race!” This isn’t an activity for the athletically gifted, intellectually blessed or the strategically savvy. There are no props, points, or rules, but there must be at least two people playing and at least one of them has to have a racially ambiguous appearance.

I have small eyes and black hair. I’m also vertically challenged and incredibly near-sighted. These four features are apparently all that’s required of me to play “Guess Her Race!” I don’t need to run fast, drink a lot or have face cards to win. I just need to look different from the norm and all of a sudden, I’m playing.

It started when I was attending elementary school in a white bread suburb outside Chicago. Classmates would ask me all the time, “What are you?” Then they’d go through the laundry list of Asian races: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Malaysian, Filipino, Thai, etc.

This question always begets multiple answers. Because although I identify ethnically as “Chinese American,” I would always just say “Chinese” because that’s what I knew they were looking for. In the end, I knew they would just sum it up to “Asian.” For years, classmates went around introducing me to others as their “Asian friend.” So it never really mattered how I responded to their guessing games; I would still end up categorized by someone else’s terms. In that sense, I’ve lost this game almost as many times as I’ve played it.

Perhaps I’m coming across as bitter, but I assure you I’m not. The racially homogenous suburb I grew up in wasn’t a hotbed for overtly racist activity — just passive ignorance. So despite hearing the occasionally unenlightened comment, I was rarely confronted with obvious prejudice. Today, when a friend or a stranger asks me upfront about my race, it doesn’t bother me. But if I pay attention to how they ask, I become more aware of how they perceive things and what’s important to them.

My idol Tina Fey has had similar experiences regarding the long scar on the left side of her cheek. She acquired it at an early age and has detailed society’s response to it in her memoir Bossypants:

I’ve always been able to tell a lot about people by whether they ask me about my scar. Most people never ask, but if it comes up naturally somehow and I offer up the story, they are quite interested. … there’s [the] sort of person who thinks it makes them seem brave or sensitive or wonderfully direct to ask me about it right away … To these folks, let me be clear. I am not interested in acting out a TV movie with you where you befriend a girl with a scar. My whole life, people who ask about my scar within one week of knowing me have invariably turned out to be egomaniacs with average intelligence or less.

Like Fey’s scar, my Asian features are out there for the world to see. My small eyes and black hair are some of the first things people notice about me and the way they act because of them reveals their true selves. Sometimes, people will treat my appearance as an invitation to start guessing my race. It’s like they think they’re on a game show requiring them to get the right answer in 30 seconds or less. Usually these people don’t mean any offense and are just genuinely inquisitive. But then there are the egomaniacs Fey refers to…

My freshman year of college, I found myself dancing with a guy at a party. In an act of misguided foreplay, he touched my face and asked me softly, “What are you?” Something about the way his fingers grazed my cheek hinted he wasn’t inquiring about my class year, major, hometown or any of the usual stats required for a one-night stand. He was playing the game. When I told him “what I was,” he grinned lasciviously and said, “I’ve never been with an Asian before.”

I didn’t know this guy very well. I do recall he was a history major and a member of the Jewish fraternity. He could be an upstanding man for all I know, a righteous dude. Though I don’t remember much about him, I do know one thing: he did not get with an Asian girl that night. To him and anyone else looking to put down a finger in the “Asian Hook Up” round of Never Have I Ever, let me be clear: I am not interested in acting out a TV movie where you befriend a girl who is Asian. Also not too keen on acting out a porno where you hook up with one. I know; I’m no fun.

When it comes to commenting on race in America, people don’t fall neatly into categories of harmless dodos or egomaniacs of average intelligence. From my time in a homogenous suburb to a fairly homogenous college campus, I’ve learned that there are many different responses. And now, unless you’re like the Alpha Epsilon Pi brother above, I don’t roll my eyes when someone plays “Guess My Race!” with me. I’ve since recognized the importance of society acknowledging my racial and ethnic identity and recent psychological studies agree.

A 2010 study on racial colorblindness published in Psychological Inquiry indicated that colorblindness doesn’t erase racial boundaries. Instead, it allows people who are unlikely to experience racial disadvantages to “ignore racism, justify the current social order, and feel more comfortable with their relatively privileged standing in society.” And, from my experience, colorblindness doesn’t help people of color come to terms with their own identity either. Politely ignoring race doesn’t make us any closer to a post-racial society; it suppresses our ability to see others and our communities as they truly are.

But when is it acceptable to ask about racial identity? In my experience, there’s a fine line between respect and offense. I have no problem discussing my race or ethnicity when the conversation occurs naturally and respectfully. But when someone asks about it to stroke their own ego or satisfy some sort of fetish? Count me out. I guess it’s just another game I don’t play.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Ruth is building her resume with a major in Spoiled Appetites and a concentration in Mac ‘N Cheese.

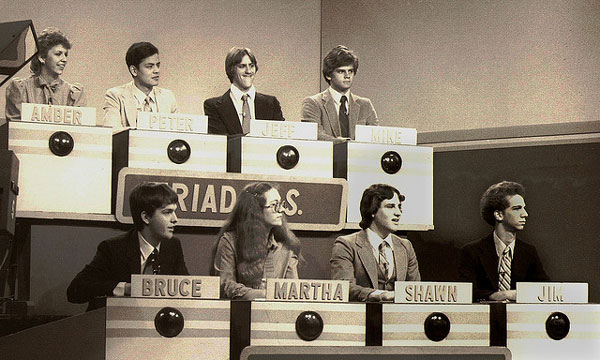

[Photo courtesy of sea turtle]