By Scott Kurashige

“What did you know and when did you know it?”

That was the question thrown in the face of Old Left supporters as reports belatedly surfaced of atrocities committed by the Soviet Union under Stalin. The allegation was that leftists in America (and beyond) were such naïve and blind ideological proponents of Russian Communism that they idealized the Soviet utopia and turned a blind eye to crimes against humanity. Of course, the right wing and the state wanted to do everything it could to discredit left-wing activism and the ex-socialists turned neocons smugly declared that they were ahead of the curve. But the liberals also were deeply invested in this line of questioning. Though they worked in coalition during the New Deal and World War II, liberals and leftists had a stark falling out during the Cold War, when (to make a long story very short) leftists accused the liberal establishment of selling out the people, kowtowing to the imperialists, and being complicit in the McCarthyist purges. So with supposed exposes of the left, the liberals sought to prove that they were the sound minds who pursued a rational course of democratic reform. A generation of scholars studying the American Communist Party from the 1950s through 1980s was caught up in this debate. Left scholars upheld the CPUSA for its challenge to U.S. Cold War foreign policy and claimed vindication as the liberals dissembled during the Vietnam War. Liberal (and to be fair, left-wing “anti-Stalinists” too) scholars denounced the CPUSA for being a puppet of Moscow that put Soviet directives ahead of its purported mission to serve the proletariat.

The debate was not irrelevant. It challenged activists to think about how they related to international “models” of revolution, how to understand the proper and improper deployment of state power, how to compare and contrast bourgeois and proletarian forms of democracy, and so on. But the debate did not speak to the issues on the minds of young activists coming of age in the 1960s/70s—whose global imaginations were inspired by China and other Third World models of revolution—nor by my generation of activists coming of age in the 1980s as struggles over apartheid, multiculturalism, and US intervention in Latin America took center stage. Robin Kelley’s first book Hammer and Hoe showed us how to look at the history of the left from a grassroots perspective: the Communist Party could serve as a symbolic image of an alternative to capitalism; it took stands for racial equality that the cautious civil rights groups were more reluctant to take; and it could provide vehicles for those who wanted to engage in mass organizing against Jim Crow and class exploitation. The real debate and action occurred on the ground and regardless of what happened within the USSR and CPUSA, we were part of a legacy of struggle that connected the Old Left of the 1930s and 1940s to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s to the Black Power and Third World Liberation Movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

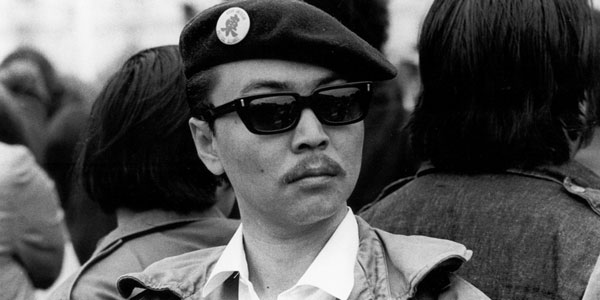

I start with this story to point out that just as every generation must discover its mission, every generation must discover its history. Today a different question has been posed at Richard Aoki, “What did you tell and when did you tell it?” The Japanese American activist and former Black Panther, Aoki has been named as an FBI informer by author Seth Rosenfeld in his new book Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power. For a different historical moment, a different connection is being used to discredit and disgrace a different radical activist and the movements he was connected to. But there are some strikingly similar patterns here too—radicalism by people of color is portrayed as something (mis)guided by an external force and left-wing politics are delegitimized while liberalism is offered as a more rational, sound, and democratic approach to social reform.

Aoki is not alive today to answer. When asked by Rosenfeld, he repeatedly denied being an informant and that Rosenfeld was wrong. Once again, the debate is not irrelevant. Rosenfeld’s allegation is an explosive one, and the history of FBI attacks on activists is long and growing. The evidence that Aoki (or any other prominent radical leader) was an FBI informant should be examined by those with expertise on or personal knowledge of the subject. This can’t happen overnight, and I’m waiting to hear a full response from all those folks with much more personal and scholarly connections to Aoki and the Panthers than I have. This includes, among many others, his executor Harvey Dong, biographer Diane Fujino, and scholars of Panther history like Donna Murch.

What I most want to stress is that we need to make sure to place the debate within the broader and proper historical and political contexts it deserves. That’s not something that Rosenfeld has done. On the surface, Rosenfeld might appear sympathetic to the movement because he’s critical of the FBI and one of his primary sources is an ex-FBI agent who has denounced COINTELPRO and supported activist claims against the government. But his research is insufficient, his analysis is frequently flawed, and he has acted in a manipulative and self-serving manner. As I will detail Rosenfeld has violated basic standards of sound historical research and journalist reporting. He also harbors a conspiratorial way of thinking and a political perspective that makes his characterizations of Aoki, the Panthers, and the Third World Liberation Front all suspect. He seeks to defend liberalism while generally discrediting late 1960s radicals of color as violent extremists who set back the gains attained during the earlier era of liberal hegemony. That’s why we need to flip the script. We need to go beyond the narrow question of “what did you tell and when did you tell it” and keep the broader focus of grassroots organizing and movement building at the center of our concerns.

I want to be clear about what I am and am not doing here. I’m not doing a full book review, and my analysis is necessarily provisional. Normally I’d wait for more evidence and interviews to come out, but this is a different case. When an author makes sensational claims in a short excerpt (just like Amy Chua did) that gets wide coverage, we need to respond with what we have to work with right now. So this is largely a review of the controversy sparked by Rosenfeld’s article on Aoki (which he published with a related video and timeline by the Center for Investigative Reporting) accompanied by a quick but incomplete reading of the most relevant parts of the book and footnotes.

1. THE ALLEGATION

Rosenfeld says he interviewed a former FBI agent named Burney Threadgill, who claims to have trained Aoki to be an informant in the late 1950s—around the time he graduated from high school. Aoki is alleged to have given reports on the Communist Party, the Socialist Workers Party, and student activists. Threadgill says he worked with Aoki until 1965 then handed him off to another unnamed agent.*

Rosenfeld also says that Aoki was still an FBI informant as a member of the Black Panthers in 1967, according to one FBI document that blacks out the name of an informant coded as T-2 but does not censor a parenthetical reference and a note in an adjacent column that links T-2 to Richard Matsui (sic—his middle name was Masato) Aoki. In the book, Rosenfeld says the November 1967 report also states that Aoki (actually it’s T-2 giving the report but Rosenfeld has already concluded T-2 is Aoki) reported to the FBI in May 1967 that he had joined the BPP and was “minister of education.”

Additionally, Rosenfeld says that former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen reviewed his evidence and concluded that Aoki was an informant.

Finally, Rosenfeld cites an interview with Aoki in which he repeatedly denies having been an informant. But he also asserts that Aoki’s added wording that can be taken as “suggestive statements” he was an informer and “an explanation” as to why he was an informer.

There are no documents to backup up the deceased Threadgill, who could have outright mistaken Aoki for another informant he trained—name me an Asian American who hasn’t been mistaken for another Asian by a white person. Nonetheless, if Threadgill’s interview can be found to be credible by corroborating evidence, this is historically significant and should be studied further. We know that in the aftermath of WWII, young Japanese Americans were a bundle of contradictions—still facing intense racism but also being embraced as a model minority. Richard embodied this contradiction—he was a stellar student but also got into fights and trouble with the law. He joined the army in the 1950s ready to be a gung-ho soldier but was discharged and then became a staunch opponent of the Vietnam War. By his own admission, Aoki was politically backwards in the 1950s. Thus, Rosenfeld says that Aoki fit the profile of someone who could have agreed under duress to do informant work in a deal to avoid prison time. This is circumstantial evidence, but at least here—unlike all of this discussion of the late 1960s—it may be consistent with Rosenfeld’s claim.

What we do know conclusively is that Aoki went through a transformation from the 1950s politically naïve youth to a 1960s committed radical. What should we make of this? Rosenfeld attributes all of Aoki’s radical actions in the 1960s to his being an FBI informant. Perhaps further evidence will prove him right, but the burden of proof is on him. Another possibility is that Rosenfeld is dead wrong. Aoki was never an FBI informant, and his political transformation was comparable to what thousands of Japanese Americans and people of color genuinely went through in the 1960s. A third possibility is that Rosenfeld is partially correct: that a checkered past in the 1950s—with the cops, the military, and/or the FBI but not necessarily all of them—made Aoki more angry at the cops, the government, and the capitalist system and fueled his militancy in the 1960s. Or perhaps there’s even another possibility—that if Aoki was forced to maintain a secret relationship with the FBI, he tried to turn it to his or the Panthers’ advantage by spying or reporting on what the FBI was doing. As a sixties activist suggested to me, there were “double agents” who were part of the movement—some with divided loyalties but some with purported full loyalty to the movement that tried to outgame the cops and FBI.

The point is that all we can do is engage in speculation at this point. In reality much of what professional historians do is responsible speculation—emphasis on the word responsible. You should do as much research as possible, only draw conclusions to the extent they are supported by evidence, and consider all alternative possibilities. This is not what Rosenfeld has done. His claim may prove to have some validity, but it may also prove to be false. The point is that he is making much stronger allegations and insinuations than what is supported by evidence and not doing research or contextualization to highlight other plausible conclusions. He has treated those who knew Aoki best as opponents, keeping them at arm’s distance from his research rather than viewing them as vital sources to give him a fuller picture of Aoki and historical context.

We must understand that Rosenfeld thinks like a conspiracy theorist. That doesn’t mean he’s entirely wrong. There was certainly an FBI conspiracy to destroy the Panthers and attack movement activists. And even the most off the wall UFO conspiracy theories probably have some purpose—e.g. the government may not be hiding alien bodies and spaceships but it’s certainly developed secret military weaponry it doesn’t want revealed.

Rosenfeld’s problem is he wants to fit all of history neatly into his conspiracy theory.

Rosenfeld’s reliance on former FBI agent Wesley Swearingen is most sketchy. Swearingen is an important witness in general—he has renounced his former work with the FBI and sought to expose COINTELPRO. But Swearingen is also on a quest to uncover conspiracies. He’s aided Geronimo Pratt and the survivors of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, but his greatest notoriety comes from a lifelong quest to prove that Lee Harvey Oswald did not kill John F. Kennedy. (Thanks to Harvey Dong for pointing me to Swearingen’s website www.oswalddidnotkilljfk.com.) Most importantly, unlike Threadgill, Swearingen does not claim a connection to Aoki. It’s fine that he condemns COINTELPRO (and maybe the FBI is also hiding what it knows about the JFK assassination), but Swearingen offers no insight one way or the other in the matter of Aoki—except to offer this ludicrous comment posing as expert testimony:

“Someone like Aoki is perfect to be in a Black Panther Party, because I understand he is Japanese,” he said. “Hey, nobody is going to guess – he’s in the Black Panther Party; nobody is going to guess that he might be an informant.”

While Rosenfeld tried to do so on Democracy Now, there’s no way he can spin this to his advantage. Who in their right mind would think that a Japanese American would be the perfect person to infiltrate the Panthers? You would immediately stick at out and arouse suspicion as to why you were there and where your loyalties really lay. Swearingen, on this specific point, clearly doesn’t know what he’s talking about, has no real knowledge of Aoki, and has apparently never heard of the model minority stereotype which marked Japanese Americans as the antithesis of black radicalism. For Rosenfeld to use this quote as “proof” is spurious, irresponsible, and racist, casting a pall of suspicion over the authenticity of any Japanese Americans (the “perfect” informants) in the radical movement. Again, it leads one to suspect that because he lacks sufficient evidence, he is trying far too hard to make Aoki fit his conspiracy theory.

Furthermore, Rosenfeld has doctored a quote by Aoki to make readers more likely to believe he is confirming his claims. Rosenfeld writes in his initial article, “Asked if this reporter was mistaken that Aoki had been an informant, Aoki said, ‘I think you are,’ but added: ‘People change. It is complex. Layer upon layer.’” The problem is that Aoki never said this—at least not in this manner and in this context. He said, “It is complex” in response to Rosenfeld’s statement the he was “trying to understand the complexities.” As those who knew Aoki best have stated, he often times spoke with humor, irony, and allusion. All he does here is repeat what Rosenfeld said, and he could very well just be stating that history is complex but Rosenfeld’s analysis is based on simplistic logic. Perhaps more significantly, Rosenfeld has spliced disparate statements of Aoki’s together. Aoki never said “People change. It is complex.” in that immediate succession. In fact, Rosenfeld provides no recording or transcript of any kind to indicate the context in which Aoki said “People change.” Again, the question arises: if Rosenfeld was so confident that Aoki’s comments substantiated his claims, why did he feel it was necessary to slice and dice his words and rearrange them to suit his agenda?

We need to review more real evidence. The most damning evidence that Aoki was an informer is Threadgill’s interview, but even that, if true, only substantiates Aoki being an informant until 1965. Rosenfeld focuses on Aoki not where his evidence, if less than definitive, is at least relatively strongest (up to 1965) but instead where it is weakest and flimsiest (1965-69) because that’s what best serves the story he wants to tell. The 1967 FBI document—the only one cited by Rosenfeld—is ambiguous. As Diane Fujino pointed out, “T-2” could refer to an informant assigned to Aoki or a wiretap placed on Aoki. And there’s nothing else for Rosenfeld to stand on. But again, even if Rosenfeld’s interpretation of the 1967 document is provisionally correct, he has no basis for treating it as if it’s conclusive and absolutely no basis for characterizing Aoki as an informant during the 1968-69 ethnic studies strike at UC Berkeley.

Rosenfeld and Swearingen say the FBI is withholding further documentation because it does not want to reveal the extent of Aoki’s work as an informant. To be certain, we do need to press the FBI to release these documents. The FBI is definitely guilty of hiding its secrets and dirty tricks. But Rosenfeld wants us to take a big leap and see that as evidence that Aoki’s work with the Panthers must be part of a bigger FBI conspiracy. How can we be certain what these documents would reveal? It’s just as plausible that the FBI does not want to release more documents because the evidence generally implicates the FBI in nefarious acts against the Panthers rather than offering more specific evidence implicating Aoki. Or again, perhaps the issue is “complex” in ways we and certainly Rosenfeld have yet to consider.

*I need to clarify one thing here. When Rosenfeld released his story on August 20, 2012, all kinds of speculation and discussion was flying through the air. The book was not out; I had no idea who Rosenfeld was; I had yet to see all his evidence; and I had yet to reach anyone who was close to Aoki or a scholarly expert on the Panthers. In the midst of a discussion with friends on Facebook, I wrote a note with some initial thoughts that was reposted on the web without my knowledge. The main emphasis was that we needed to wait and see more evidence, especially because Rosenfeld seemed to be making hasty and spurious judgments. The main question, dictated by the headlines, was whether Aoki gave the Panthers guns and did other work for the Panthers at the direction of the FBI. I pointed out many reasons why this seemed implausible based on what I knew about that history and how Rosenfeld was distorting it. There’s one statement I would clearly have not have written had I known my words would go beyond the Facebook discussion. In response to the Threadgill assertion that Aoki was an informant from the late 1950s to 1965, I wrote “Let’s accept this.” As should hopefully be clear from the context, I was saying “let’s accept this for the sake of argument and see if Rosenfeld’s claim holds up.” In other words, even if you concede that Rosenfeld is correct in this one regard, there’s no way his whole argument can be substantiated. But as I have always specified, none of Rosenfeld’s evidence is conclusive and all his claims about Aoki must be held to greater scrutiny.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Scott Kurashige has been a campus and community activist since the late 1980s, was based in Los Angeles in the 1990s, and has been primarily based in Detroit since 2000. He is the author of The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles and co-author with Grace Lee Boggs of The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century. He is also director of the Asian/Pacific Islander American Studies Program and a professor of American Culture and History at the University of Michigan.

Check back tomorrow for Part 2 of Scott’s three-part piece on the Richard Aoki debate.