[In 2009, the decades-long civil war in Sri Lanka between the terrorist LTTE or Tamil Tigers and Sri Lankan Government finally ended, but left behind a legacy of war that endures, further complicated by global climate change. In 2012, Johnny C traveled there to cover the forces of war, globalization, and climate change. Some names and organizations have been changed to protect the identities of those who participated in the events of this series.]

I entered Velupillial Prabhakara, the LTTE leader’s home converted into a museum for civilians to see the lavish environment he lived in while children were kidnapped and forced to serve in his armed forces. My attempts at gonzo material to write truthfully about everything I saw and did were dashed against the rocks in the first five minutes: I thought it would be Hunter S. Thompson-esque to piss in his still-functioning toilet in his home and not flush, to show just what I thought of the son of a bitch, only to find a few golden nuggets that revealed others felt the same way about him too. I slammed the lid shut and instead decided I’d look at juxtaposition of expensive toys for his children in the same space as the weapons his men were armed with, from mines, guns, knives, and other explosives to be prepared in case the Government came. It was toys for both the little men and the big boys in the same room.

I descended further without incident into his bunker below his home and as the few other aid workers and tourists stayed outside to take pictures of the front of his home, I walked into his office and imagined what it must feel like to sit in a space no larger than a hostel room was, at his desk, and make decisions that led to the deaths and displacement of thousands of civilians, created orphans and widows, and took away jobs, and blew up a water tower to deprive everyone of clean drinking water to spite the army.

“So this is what it feels like to be an asshole” I thought.

I thought about the widow I had interviewed earlier that week. One of the NGOs had given her and her community members a new lease on life: free shelter from one, life skills from another and work weaving to support her and her only child. When I first met her, she and the whole room were nothing but smiles, especially because I spent the better part of the introduction prior to the interview playing games with the kids and showing the women I may be a man but I don’t bite, a little heart to heart so that they could be more comfortable in front of the camera. It was then I realized that in making her more comfortable around me, the fullness of her 24 years of life came out as she remembered marrying the boy she loved and having a son whom he never met before he was forced to join the Tamil Tigers, how her home was shelled and she had to stay in the displacement camps, and that returning “home” was going back to the same province but nowhere near where she grew up and most of her family dead–that there was now only her and her son, and her husband. I thought of how when we asked what we could do for her, and she broke down into tears and said “I am no widow; I want my husband.”

My eyebrows furled and fists tightened, and the rage pulsated through the veins that became more visible in my forehead and arms as my blood boiled in 42-degree Celsius heat. It was probably closer to 38 degrees, but the rage likely turned it up a few notches.

“I want my father back” some orphans would say, “I want my legs back” some shelling and landmine victims said, and “I want my life back” one girl who had been a child soldier said.

The lives of the children and youth destroyed by one man were further complicated by the forces of separatism and globalization: many of them felt the biggest hope was to flee to Australia and get refugee status without understanding a thing at all about illegal immigration and what they could or would actually do to the thousands who try to go each year. Even if there are more jobs in Sri Lanka now, most of those are in the Sinhalese-speaking south, and most Tamils from the north don’t speak the language or have the education or job skills that would allow them to make that transition. Add the cultural layer that people who still have their families would not want to leave their homes and have their fates–all the way from arranged marriages to career decisions–dictated by their parents, and you don’t have any easy solutions, even when NGOs are bringing work up north from weaving to food processing and agriculture work. And agricultural work was further complicated because of the country’s weird weather and two monsoon and two dry seasons depending on what part of the island you were on, again made worse when global climate change led to longer dry seasons that made growing crops harder and having enough to eat during that time pure agony.

It was a strange contradiction of not wanting (let alone being able to) leave their families and communities for more opportunities down south but a willingness to immediately bring everyone onto a ship and risk everything going to Australia for a new lease on life, knowing they could be turned back or subject to harsh realities of life in a land where they don’t even speak the language.

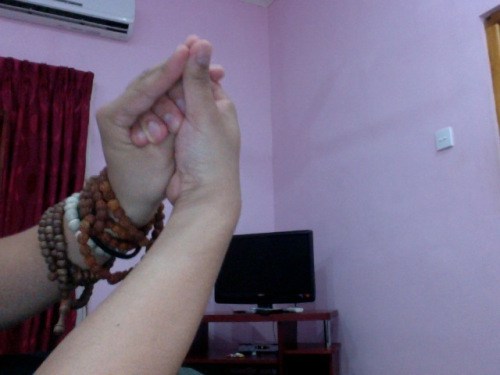

As I walked out of house, Sam and the driver pulled out some pictures for me to look at that they had taken after I had left a few sites with the orphans and widows. I looked and realized I had definitely done something good, even if not much. I showed the widow whom I was thinking of an old Yoga technique my guru taught me with my hands, a little physical meditation that would instantly calm anyone’s heavy sadness and anxiety. With your right hand, grab your left thumb; rest your left ring and little fingers on the right knuckle; then press the right thumb against the left index and middle fingers’ tips, and you have the Shankh mudra (sacred hand gesture), which you then hold to your heart. She did that and it brought her a little peace, and when I went back into the center after remembering I had left my notebook inside, she was teaching the other women and children how to do it as well. Word had gotten around, and in a few of the orphanages, schools, and work centers we passed by, people had all learned what I had taught them and were teaching each other. I did one small act of kindness, even if it was a drop in the ocean, and saw the karmic ripple effect not unlike what I saw when I saw the movie Cloud Atlas six times was right there in pictures, as the finale theme played in my head: people all over the north had been doing the Shankh mudra, and children were teaching it to their parents and peers.

“A drop in the ocean” Adam Ewing said. “Yet what is the ocean but a multitude of drops?”

End of Part 2

- Previous: Strange Serendipities in Ceylon (Part 1)

- Coming up next week: Strange Serendipities in Ceylon (Part 3)