By Jasmine Jia

June 4, 2013: It is raining in Beijing. It never fails to rain on June 4th, almost every year since 1989.

A Chinese idiom, 老天有眼 (lao3 tian1 you3 yan3) means that God has finally spoken out Himself. The idiom is used to express many citizens’ and students’ opinion on how the Chinese government handled the June 4th-led political demonstration.

Tiananmen Square was just a vague picture for me since I was in 6th grade when the movement took place in 1989. I recall that the only information source during that June was the CCTV (the Chinese Central Television), and it condemned the movement as a counter-revolution riot. Until I entered Peking University (北京大学) in 1996, a university remembered as a leading proponent of the June 4th movement, I knew very little about the incident.

At Peking University, my professors told us the stories of what happened to them when they were in class. Their narrative is spun and netted with sadness. Their sadness has since haunted me and it became a mission of mine to search for the truth, to uncover the facts and put together the real story for myself. There were no recorded documents, nothing in writing, and nothing in any of the libraries.

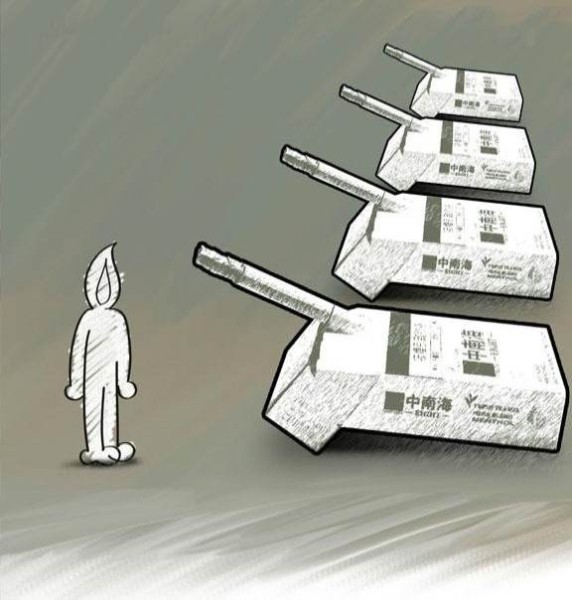

June 4th, which is how we Chinese refer to the incident, is ascribed as a student movement, 学潮 (xue chao). I ascribe it as a sad romantic story. Liberals in China and college students fell in love with a popular girl: democracy. The authorities, the Chinese government, forbade the love and exercised its force to stamp out the fire. Since June 4th, those with the unrequited romance for democracy in China have been separated from it. All forms of discussion and remembrance of the incident are stifled.

As potent a love story as June 4th is, it is also a mystery. Many aspects of the event remain unknown and unconfirmed. It is my hope that one day, those who possess the information of what really happened on June 4th will have the courage to step forward and finally make accessible to the public, to the people of China, what happened.

The catalyst for the June 4th incident was the sudden death of Hu Yaobang in April, 1989. Hu was the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and a liberal reformer who won the popular support of the Chinese. Hu was known for his outspoken and controversial political opinions. When several professors and students in 1986 organized a protest, Deng Xiaoping ordered Hu to quash the protest and silence the students, but Hu refused. Unceremoniously, Hu then “resigned” and at the same time, issued a humiliating public confession of his “mistakes” during his leadership. He subsequently died of a heart attack at a conference where he was to speak about education reform.

After his funeral, Beijing students petitioned the government to recant the humiliating confession statement that Hu was forced to issue and clear the circumstances of his resignation. When the government proved non-responsive, 50,000 students marched toward Tiananmen Square and the march eventually escalated to what is now known as the June 4th Incident.

Several years back, I conducted a survey among the Chinese post-80s generation to get their opinion on the 1989 Tiananmen Movement. Of 998 individuals who I interviewed, only 23% stated that they even knew what the movement was. I was not surprised to see this low rate, considering the lack of the accessible information on the incident and the change of the Chinese youth after 1989. Among those who have knowledge of the movement, they either gather their information from family members or from friends. The news goes mouth by mouth, and generation by generation.

It is a tragedy that today’s youth have few if any thoughts on what the Tiananmen Square Movement was and what drove the students to demonstrate. We must remember the date. We must never allow it to fall into obscurity or let the efforts of those students in 1989 go in vain. China has made great leaps forward in its economic growth, but it has hardly made a dent in profound political reform.

It is a sunny day here in California where I am, as usual, but today, my heart is rainy for those who had died for China’s democracy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Jasmine Jia holds a doctorate in politics and international relations from USC where she specialized in comparative politics, international political economy and methodology. The above-referenced survey she conducted was part of her dissertation work on political identity and political participation of the post-80s generation Chinese. She obtained her M.A. and B.A. from Peking University, where she studied economics and political science.

Image Credit: Jia Jia