While 8asians has covered Asian Americans and college admissions over the years, a recent article from the data services company Priceonomics takes a data driven approach to summarize the arguments in the debate whether elite colleges discriminate against Asian American in admissions. This article does a decent job of trying to look at both sides. It brought out some points that I hadn’t thought about, although I think it missed a number of key points which I will point out below.

Evidence for Discrimination

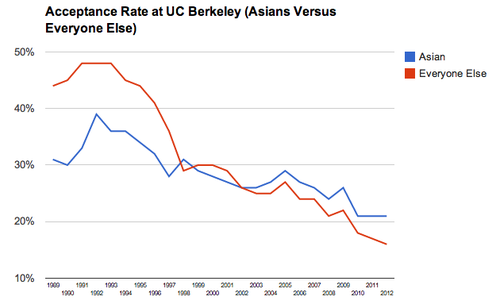

The article first explores data showing discrimination against Asians. Author Robin Dhar points to the work by Thomas Espenshade finding that Asian Americans need higher SAT scores to get into elite private colleges. Dhar also provides a graph of acceptance rates (below) showing that Asian admission rates to UC Berkeley were much lower than every other ethnic groups’ rate before 1996 but became higher after the passing Proposition 209, which banned affirmative action. I have seen some arguments for SCA5 that said that Prop 209 made no difference in Asian American admission rates, saying that Asian American admission rates declined after it passed. While it is true that Asian American admission rates declined after 209’s passing, admissions has gotten harder for every ethnic group. The best analysis in this case is to compare Asian admissions against everyone else’s admissions rates. Asian Admissions rates did improve relative to all other groups.

(graphic credit: Priceonomics)

Evidence against Discrimination

The author says he had trouble finding much data that contradicts the argument. He does mention that Espenshade stops short of saying that the Ivy League discriminate, saying there are other factors that elite colleges consider, like essays, athletic abilities, and legacy status. Arguments against discrimination that center about holistic review imply that Asians Americans are deficient in other areas than test scores. Other counter arguments say Asians are not populous in two key groups – recruited athletes and children of alumni. This argument used to defend Harvard in a civil rights investigation in 1990. As Shar points out, that doesn’t explain why the Asian American numbers at Harvard are the same after more than 20 years of growth in the Asian American share of the US population.

Some Excellent Points

The article raises some interesting issues. It points outs that Ivy League schools say that they don’t discriminate but provide no data which could back up their point. The Espenshade book relies on data over 15 years old (the last time that Ivy colleges made complete admissions data available), but Dhar says that universities refuse to release any recent data to either validate it or refute contentions of discrimination. I like how he calls holistic admissions a “subjective black box that could be used for good or evil.” Dhar points that holistic review, hailed by pro-affirmative groups as the best way to do admissions, has a history based in the desire by Ivy League schools to lower the number of Jews on their campuses. Legacy based admissions became another way to reduce the number of Jewish students.

Points missed

The author works for a data company, so I was disappointed when he used a technique that is often used to manipulate opinion – not showing zero on the Y-Axis on the graph shown above. Starting the Y-Axis at 10 makes the difference between Asians and “Everyone Else” more pronounced. While describing arguments against the existence of discrimination, he mentions that test scores are only one factor in the calculation of “merit.” A data driven approach should have also pointed out that test scores correlate strongly to income, and that some studies show that standardized tests do not strongly predict success in college.

Another argument not described is the straightforward one described here by Dr. OiYan Poon. She says simply that at the elite colleges, Asian Americans are represented far more than their US population of 5%. She cites Asian American populations at Princeton being 13%, Harvard at 16%, Stanford at 22%, and U.C. Berkeley at 42%. Given that many Asian Americans do not have an adequate K-12 educations, lacking basic things like text books, is worrying about “the Asian 1%” really the best use of political energy?

While he was discussing holistic review, it would have also been good to discuss data that shows how the very presence of names that indicate minority status and gender changes the response of those making critical subjective judgments. A recent study of how professors responds to requests to discuss research opportunities shows that professors are significantly more likely to respond to white males compared to women and minorities. The greatest disparity was between white men and Chinese women, as white men generate a response rate to research queries that was 29 percentage points higher.

The Need for Transparency

Although the article is not perfect, I think it’s a decent analysis of the college admissions situation for Asian Americans based on data. I think that the most important issue it raises is that of transparency. While I do not think solely using grade/test based admissions is the best methodology, the historic use of holistic review and descriptions from admissions workers like this one and this other are worrisome. I think Dhor sums it well it well:

Many Asians believe they are being held to a different academic standard than whites. This belief might be true or false, but universities should release the data that puts the debate to rest.