Tanwi Nandini Islam’s debut novel Bright Lines is a coming-of-age story for three young girls in Brooklyn and a family trying to find itself. Ella returns home from college for the summer to see her aunt, uncle, and cousin in Brooklyn, her adopted family after her parent’s death. The girls–Ella, her cousin Charu, and their friend Maya–explore the city, boys and girls, their sexuality, their identities. Hashi and Anwar, the parents, immigrants from Bangladesh, try to balance their work and a relationship laced with the past.

Tanwi Nandini Islam’s debut novel Bright Lines is a coming-of-age story for three young girls in Brooklyn and a family trying to find itself. Ella returns home from college for the summer to see her aunt, uncle, and cousin in Brooklyn, her adopted family after her parent’s death. The girls–Ella, her cousin Charu, and their friend Maya–explore the city, boys and girls, their sexuality, their identities. Hashi and Anwar, the parents, immigrants from Bangladesh, try to balance their work and a relationship laced with the past.

The story is overflowing with plot which no overview could possibly give justice to and it is the plot that keeps the reader engaged as much as the characters who dominate. Of the several characters, Ella and Anwar are the most compelling and detailed. Their relationship also embodies the book’s thematic twists and turns about family, love, and how the past haunts the present and a search for home haunts each in a different way.

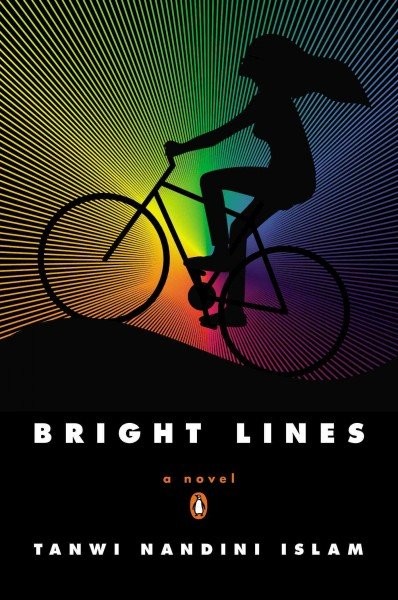

The first part of the story takes place in Brooklyn, a summer of exploration, confusion, and frustration. The girls bike around the city, seeking escape from their homes. The parents separately delve into their passions, business and otherwise. The pages are filled with friction, even amidst summer’s frivolity, and the complex web of character relations begins to emerge. The second part sends the family on vacation to Bangladesh, where the new setting refocuses the multiple identity crises in the family and they are reunited with Ella and Charu’s grandfather and uncle. With a lot packed into these pages, it is an almost overwhelming whirlwind with generations, couples, families, cousins, friends, lovers, immigrants, New Yorkers, all trying to untangle their selves and a complex web of relationships. Yet this active fervor captures the trials of growing up or growing in general in exactly that it does sometimes all happen at once.

As frequent readers may have realized, I am very interested in language, the idea of it, the flow of it, different styles, different languages, etc. etc., and so this excerpt–which captures something of growing up, but also about the corner that Bright Lines situates itself in.

It was impossible to find the words with her parents to communicate her feelings with precision and honesty. She’d tried to explain this dilemma to Maya once, but Maya dismissed this as a common affliction for all teenagers. Muslim teenagers got a score of zero on a one-to-ten scale of being able to talk about sex with their folks. But Charu felt it had to do with language. She never could express her love or her sorrow in Bangla, the language of her parents. She had English for that. If she tried to say, “I want to explore a number of relationships before I’m ready to commit myself to one person entirely,” it was like screaming into a ravine.