In April of this year, I was asked by Southern California Public Radio to do a presentation about my family as part of their new series called, Unheard LA. The following is the video from my talk, followed by my original speech (broken into two parts). Please note, the text is from the original draft of the speech, so at points is considerably different than the actual talk I gave.

https://www.facebook.com/KPCCInPerson/videos/1461691680518601/

Be sure to read, Part 1.

CHAPTER 5: The story (cont.)

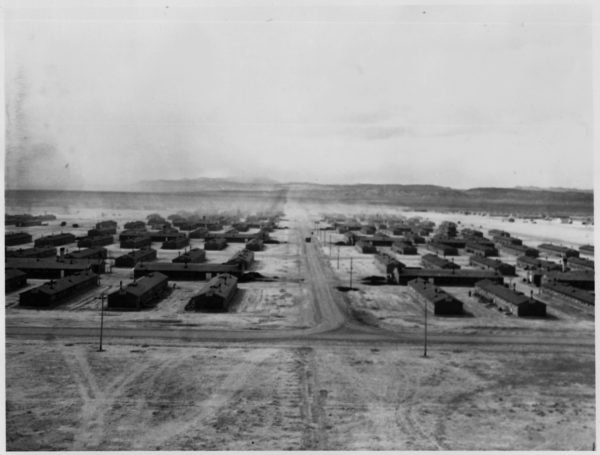

The “camp” my family was sent to was in Topaz, Utah.

Now imagine: People going from sunny and WARM Hawaii to the high deserts of Utah—where in the winter there was a snow on the ground and in the summer it was often over 100 degrees. They couldn’t have been prepared for that.

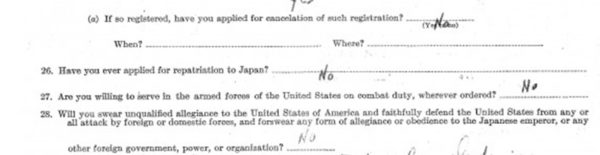

It is important not only to know where they were but why. In 1943, America needed soldiers and people to help the war effort. And there were 120,000 Japanese Americans sitting idly in these “camps.” But the problem was that the government couldn’t tell the “good” Japanese Americans versus the “bad” Japanese Americans. So, they created a loyalty questionnaire.

The two most important questions were questions 27-28.

There were only two possible answers to these questions. Yes, Yes and No, No. Answering one of them no, meant you were answering them both no. These two questions literally divided my community and its effects can still be felt today.

So why did people answer yes-yes? It’s pretty simple actually. They were loyal and willing to prove it. And they had no allegiances to any other country. The No-Nos were a bit more complicated. Some said, take me out of camp, take me out of this prison, I’m willing to answer yes, until then: No. And they believed Question 28 was a trick question, because the basic underlying assumption was that you had allegiances to another country.

How did my grandfather answer these questions? No Question 27 and No to Question 28.

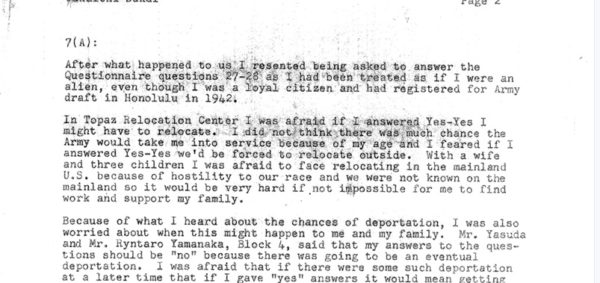

Here are my grandfather’s words on why he answered the way he did:

- As an American citizen, he was insulted.

- He thought if he answered yes-yes, he and his family would be released on the mainland where they had no friends and family and into communities where anti-Japanese sentiment prevailed.

- If they were going to be deported anyway – as my grandfather believed – a ‘yes’ answer would not look good.

And, because of his answer, they were sent to Tule Lake.

…where all the “bad” Japanese were sent.

In 1944, the US government passed a law that allowed American born citizens to renounce their citizenship voluntarily during wartime. The bill was designed to pave the way for the mass deportation of Japanese Americans after the war.

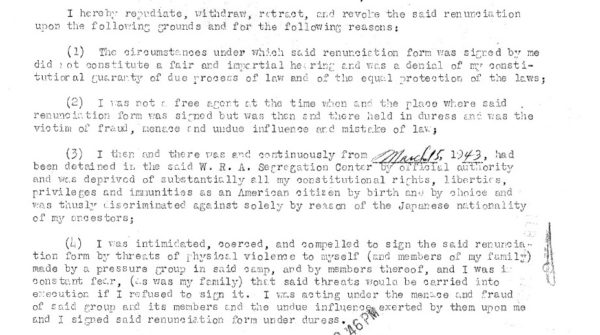

It was under this law that my grandfather (and other Japanese Americans like him) renounced his citizenship. He said he did this because he was convinced that Japanese Americans were going to be deported to Japan and it’s better to be first rather than last in line. Secondly, there were pro-Japanese factions in camps that threatened him and his family if he didn’t renounce his citizenship.

Once Tule Lake closed, they were sent to Crystal City, Texas.

This camp was for an “enemy aliens” and had to adhere to the Geneva Conventions, meaning better food and shelter than the “regular camps”. And when I looked into it, there was a swimming pool in Crystal City

After the war, my grandfather and other Japanese Americans realized renouncing their citizenship was a mistake. They worked with Wayne Collins, a wonderful lawyer from San Francisco, who said, “You can no more resign your citizenship in a time of war than you can resign from the human race.” He argued their renunciations had been the result of the unlawful detention and the terrible conditions in Tule Lake and not their decision.

My grandfather argued he was an American by birth. His rights had been violated. But he wanted to remain in the country.

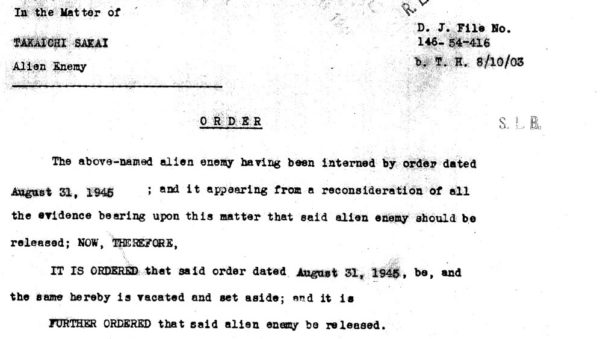

After much hand wringing, my grandfather and his family were allowed to stay…

… they were given $25 dollars each and one way tickets back to Hawaii. Their citizenship was returned to them 10 years later.

I don’t look at my grandfather’s story through rose-colored glasses. There are many disturbing things about his story. In fact, the first time I read it I thought he was a spy. Unfortunately, my grandfather passed away before I was born. I have so many questions I wish I could ask him. The most important being, did he know about Pearl Harbor.

But even without those answers, I no longer believe he was a spy. He just got caught in a wave of hysteria and was making the decisions he thought was best for him and his family. Blaming my grandfather also takes blame away from the government, who incarcerated 120,000 based entirely on their ethnicity.

Now that I know the story, I use every opportunity to pass the story to my son.

CHAPTER 6: Passing the story

It started with a trip to Manzanar when he was four.

But this was not just a one-time thing. Every time we pass places where Japanese Americans were incarcerated here in Southern California, I make sure to remind him. So that includes Santa Anita Race track, Griffith Park, Pomona Fair Grounds, and Tuna Canyon. I tell him, “this is where they locked up our people.”

This is my life’s work, to share the story of my family and others who were locked up. In fact, I constantly tell my son that we, as decadents of people who were locked up in these “camps,” have a moral responsibility to make sure that it never happens again to anyone ever. And I share it with all of you in the hopes we don’t let history repeat itself again.

Follow me on Twitter @ksakai1.